By Anne Mattina

By Anne Mattina

Professor, Stonehill College

Reading Frederick Douglass Together Research Fellow

This program is made possible by a grant from Mass Humanities, which provided funding

through “A More Perfect Union,” a special initiative of the

National Endowment for the Humanities.

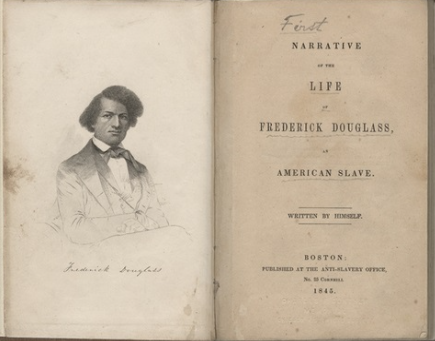

Last spring I was the proud recipient of a Reading Frederick Douglass Together Fellowship from Mass Humanities and it has been a joy tracing his legacy across the Commonwealth. It is well-known that the self-emancipated Douglass arrived in New Bedford in 1838, shortly after his escape from bondage and that he spent several very important years there working on the docks and honing his skills as an orator. But he did not come to Massachusetts alone – he arrived with his bride of several weeks Anna Murray and subsequently three of their five children, Rosetta, Lewis, and Frederick, Jr. were born in the city. It was here that Frederick’s reputation as a speaker spread beyond the churches where he could be found exhorting the Black community during those first years of freedom.

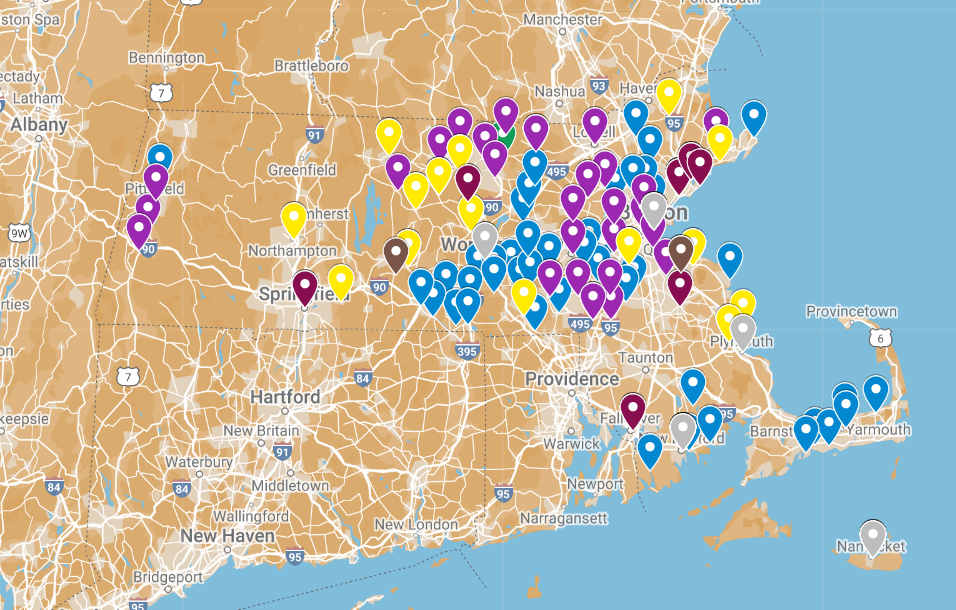

Click on the “View Larger Map” icon in the upper right hand corner of the maps below. You can see where Douglass spoke while he and his family lived in Massachusetts. Once you view the full screen map, you can use the buttons on the left hand side of each map to toggle on and off different years.

White abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison learned of Douglass’ compelling story and oratorical power while attending the annual meeting of the Bristol County Anti-Slavery Society in 1841. They sought him out to join them on their travels to Nantucket for another convention and the invitation was extended to Anna Douglass as well. Nantucket is where he delivered his first address to a mixed-race audience. He was hired on the spot by John Collins, president of the Massachusetts Anti-slavery Society (MASS) and quickly set out to join a team of lecturers championing the cause. His was an extraordinary life and as such, it has been very well-documented with multiple biographies, articles and exhibitions.

My goal for this fellowship has been to shine a light on Douglass’ time in the Commonwealth both as a resident and visitor during the period from 1838 to 1863. My research includes documenting where he spoke, how he was received, what he experienced and how he is remembered nearly two centuries later.

Here are some of the highlights of what I have learned thus far:

- Frederick Douglass was only 20 years old when he arrived in New Bedford, and began his public career as a paid agent of MASS at 23.

- Douglass is memorialized throughout New Bedford and Nantucket with plaques and portraits found in multiple public spaces in both places. In 2023, New Bedford opened Abolition Row Park, located across the street from the Nathan & Polly Johnson’s home where Frederick & Anna lived and were welcomed into the Black community. The park, which consists of a small plaza, is anchored by a magnificent statue of young Douglass.

- New Bedford held a cherished place in the Douglass family’s heart long after they moved away in 1841. In 1848 he reported in his newly launched newspaper The North Star that he was to lecture in New Bedford, “the only town in which I’ve felt myself really at home since I left the South.” (Feb. 11, 1848, p.2).

- One week after the close of the Nantucket Convention, Frederick could be found in the company of John Collins in Millbury addressing the Quarterly Meeting of MASS. Shortly after they visited Groton, and then were on to Abington where Douglass delivered four addresses in different parts of that abolitionist stronghold.

- In early October, Frederick delivered his first recorded speech in Lynn, a city which would become his family’s second home in the Bay State. His presence is memorialized throughout Lynn with a massive and colorful mural and a marker on the town common indicating where he delivered his early address. Additionally there is an amphitheater named for him on the common. It was also as a resident of Lynn that Douglass began to challenge segregation in public transportation, refusing to be moved from the main passenger section of the local street car.

- By the end of 1842, Frederick had spoken in as many as 50 different towns in the Commonwealth, several of them multiple times. His travels took him from Nantucket to Lanesborough and also included appearances in New Hampshire and Rhode Island.

- One of the things that many of these towns had in common besides active anti-slavery associations was a strong Quaker presence, something not often mentioned in discussions about Massachusetts abolition. The small town of Pelham for example, was the birthplace of Quaker school teacher Abby Kelley, another leading light among movement orators. Effingham Capron, a Quaker mill owner from Uxbridge, held leadership positions in both state and national anti-slavery associations. He hosted Douglass and others of the party in his home when they came to speak, as did Quaker Bourne Spooner of Plymouth.

- Anti-slavery Societies were often denied access to public buildings when meetings with MASS agents were planned. Instead, speakers including Frederick Douglass often addressed crowds in outdoor spaces. Among the more prominent were Harmony Grove in Framingham (where William Lloyd Garrison infamously set a copy of the American Constitution on fire); Tranquility Grove in Hingham; the Lynn & Grafton Town Commons; Island Grove in Abington and Nelson’s Grove in Hopedale.

- Little notice was given of Douglass’ appearance in Grafton in 1842 and when he arrived not only were public speaking venues closed to him, not much of an audience had gathered. Undeterred, he borrowed a dinner bell from the Kirby Hotel and went through the streets ringing it, proclaiming “Notice! Frederick Douglass, recently a slave, will lecture on American Slavery, on Grafton Common, this evening at 7 o’clock. Those who would like to hear of the workings of slavery by one of the slaves are respectfully invited to attend.”

- In 1843, Douglass, along with fellow fugitive George Latimer and Black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond of Salem, were appointed to a committee of the MASS to deliver a letter to President John Tyler imploring him to liberate those he held in bondage. This was to take place when the president visited Boston in June for the dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument. The letter was instead sent directly to the President who did not reply. He was, however, driven to the dedication by a man he held as a slave.

- At Frederick Douglass’ request, the utopian community of Hopedale welcomed fugitive Rosetta Hall as a member of their community in 1845. According to Aidan Ballou’s History of the Hopedale Community, Rosetta was a “protege” of Frederick’s “the two having known each other as slaves.” Douglass’ first visit to the community was in April of 1842 “all hearts were moved and melted,” Ballou observed.

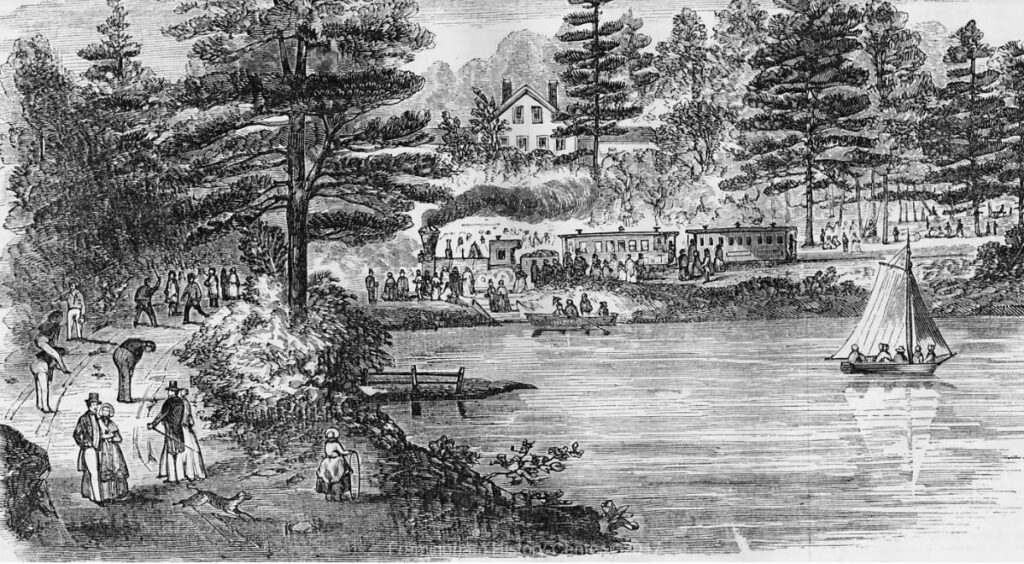

- Between 6,000 and 10,000 abolitionists gathered together in Hingham in 1844 for what became known as The Great Abolitionist Picnic marking the 10th anniversary of the end of slavery in the British West Indies. People arrived by train, horse and carriage as well as by boat. Frederick Douglass arrived with William Lloyd Garrison on a steamboat from Boston where they were met by a crowd and joined them in a parade to Tranquility Grove. Douglass addressed the throng in the afternoon and a massive repast was shared. Music provided by the famous Hutchinson Singers entertained during intervals between speeches. It was thought to be the largest anti-slavery gathering of its kind.

- In May, 1844 Douglass delivered a speech in Northampton and had his first encounter with Sojourner Truth in the village of Florence. Later in 1952 a memorable exchange occurred between them when Truth interrupted Douglass while he was speaking at an Ohio anti-slavery convention. Frederick had split from the Garrisonian wing of the movement and now was now recognizing that violence might be needed to combat slavery. From the audience, Truth asked, “Is God gone?”* The two would have an uneasy alliance throughout their lives.

- Douglass met John Brown for the first time at his home in Springfield in 1847. Brown had sent him an urgent message to Douglass inviting him to call. It was here that Frederick first learned of Brown’s plan to liberate the enslaved in Virginia. It was also the beginning of a very strong friendship between the two men.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe welcomed Federick to her home in Andover in 1853 as she wished to reconcile Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. She did not succeed in that regard. After the meeting Stowe wrote to Garrison about Douglass, “I am satisfied that his change of sentiments was not a mere political one but a genuine growth of his own conviction. A vigorous reflective mind like his cast among those holding new sentiments is naturally led to modified views.”

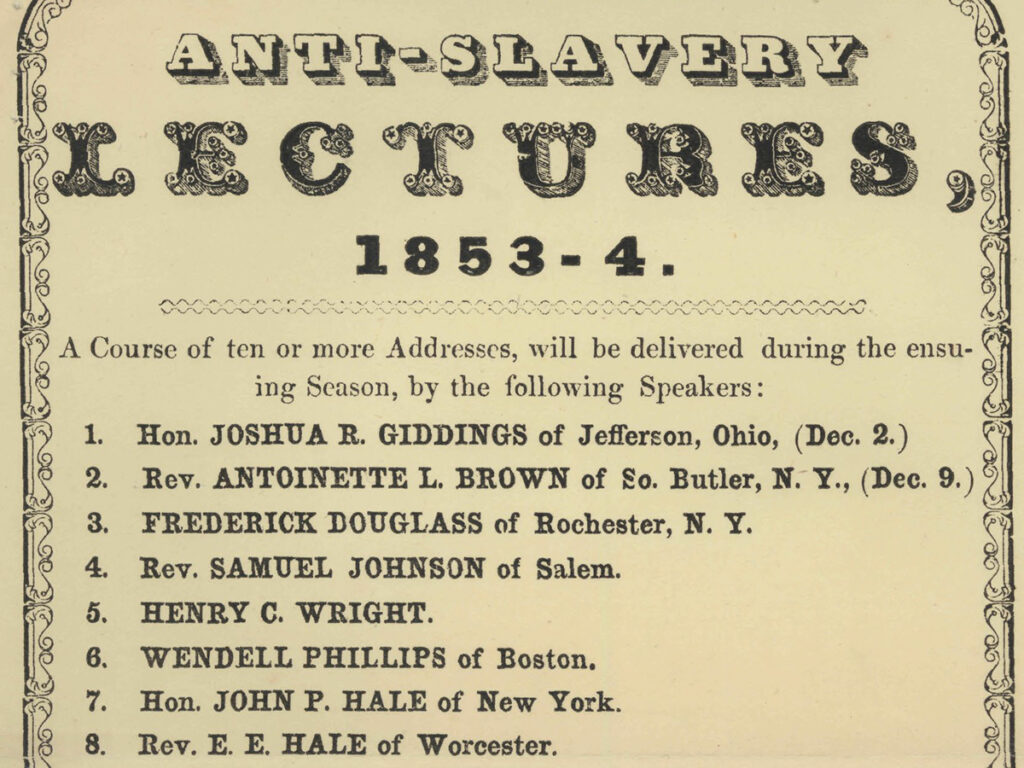

Frederick Douglass would return again and again to Massachusetts in the years leading up to the Civil War and beyond. To date, I have identified 120 different cities and towns in which he spoke in the Commonwealth between 1841 and 1861. Though a citizen of Rochester, NY after 1848 and no longer affiliated with MASS and the Garrisonian wing of the movement, he remained much in demand across the state lecturing from Westfield to Falmouth.

Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew recognized the power of Douglass’ persuasion and hired him in 1863 to recruit Black men into the first regiments open to them in the Civil War. Not only was Douglass successful in raising two companies, his own sons Lewis and Charles volunteered to fight. Lewis was a member of the famed 54th regiment and survived the horrific battle at Fort Wagner, South Carolina. Though Charles became ill and did not see action with the 54th, he later re-enlisted and became 1st sergeant in the 5th Massachusetts Cavalry. Frederick, Jr. worked with his father recruiting and held the rank of sergeant in the 25th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment.

Even after the Civil War, Frederick Douglass found time to visit the Bay State, often being invited to abolitionist reunions and anniversary celebrations. In 1874, while on a trip to deliver a speech at Cosmian Hall in Northampton, Douglass made it a point to return to Grafton where he had been denied access to speaking venues in 1842. Though he had come full circle, it was not his last Massachusetts visit, indeed he lived 21 years longer, passing away in February, 1895.

While this essay has come to its conclusion, my research on Frederick Douglass and “the grand old Commonwealth” as he referred to it, continues. There is much more to be discovered and shared regarding one of our finest citizens.

* sometimes quoted as “Is God dead?”

Listen to Professor Mattina discuss her research in the Reading Frederick Douglass Together webinar below. Her segment begins at the 25:00 minute mark.