By William Murphy

My favorite combat position was prone by an ancient elm tree that, despite the exposed roots digging into my skinny ribcage, afforded perfect sightlines and shooting angles. An adjacent stockade fence provided both cover from detection and shade from the searing sun. Typically, the tarmac straight ahead was clear of any vehicles or machinery to obstruct my shots. The dense Old World forest and vegetation twenty yards to the rear were my sole escape route to a stream that I could easily ford or speed down in a raft hidden a short distance downstream. I had used this position successfully many times on selected human targets. On other operations I used the same basic procedures without fail. I did my homework, I practiced, I was patient, I was equipped, and, most importantly, I wanted to succeed. I was not going to just go through the motions.

Most operations ended the same way. “Billy, Joey! Time for dinner.”

Once in a while, an operation ended when the intended target, my brother Joey, claimed he shot and killed me first when he hadn’t. In those instances, the game degenerated into a yelling match—or more—with mutual declarations to never play again. The statute of limitations on those claims covered the period until the next sunrise.

Both my parents were World War II veterans. Dad was an army tank commander under General Patton in the Battle of the Bulge. Mom operated Morse code for the navy. After the war they went to work for the Veterans Administration where they met, got married, and moved into a second-floor walkup apartment at the corner of Columbia Road and Blue Hill Avenue. I was baptized at St. Hughes in Grove Hall. In 1950, the Dorchester Murphys, with two sons in tow, moved into a two-bedroom Cape Cod–style house (purchased with a VA-backed loan) on Rockcroft Road, a dead-end street in Weymouth. Mom’s mother, Ma Mulligan from Roxbury, moved into the dining room, thus converting the house to a three bedroom.

Rockcroft was one of many rural streets that were reshaped into small lots to accommodate the families of war veterans such as Bill Murphy and Ann Mulligan Murphy. Across the street was a meadow and a field and a forest. In sight of 39 Rockcroft Road were two abandoned stone buildings, the remnants of a farmhouse with two and a half walls and part of its chimney beckoning curious kids. Some type of watering hole for farm animals, with a cobbled slope surrounded by stone retaining walls, provided a setting for games of cowboys and the like. The structures were now overgrown with waist-high grasses and a sparse mixture of young seedlings, long-dead tree trunks, and two mature apple trees. This landscape provided venues for contests of tag and hide-and-seek that kept children busy and often late for dinner.

As a dead-end street, Rockcroft was home field to continuous stickball, touch football, and street hockey games. Behind our house was Mill River, composed more of pools of standing water interspersed with slowly moving rivulets—ten feet at its widest, four feet at its deepest. The smell was more akin to a swamp than a river, but it was upstream from the lumber mill. Still, at that spot and at that time in history, it was free of pollutants. Hardly Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, but it was the scene of many gambols and gambles. During the postwar housing boom, masons on the nearby housing subdivision project were aggravated when their cement mixing tubs went missing, appropriated for riverboat duty by Rockcroft boatmen. No matter what activity was afoot, Mill River was more often than not the scene of noncriminal violations of the come-home-for-dinner, don’t-get-your-pants-wet, no-throwing-rocks, don’t-play-with-matches regulations in force at the time.

My parents continued their government service with Dad a mailman for the US Post Office and Mom a clerk for the US Department of Defense. Commuting into Boston each day, they took a chance that leaving latchkey kids at home in the suburbs was safer than Mom staying at home and letting her two boys out on the streets of Dorchester. Dad clearly intended to shield his two sons from the inconveniences and horrors that he had encountered in the war. He strongly preached that we should not join the armed services—certainly not as a draftee, infantry, or enlisted man. Mom, in her typical reserved manner, subtly got across her message that she considered military service a monumental waste of time and life—although considered necessary in her time. They both did their best to guard us from the dangers lurking beyond Rockcroft Road. They both nurtured us toward pursuing a college education and public service.

As Greenwich Village folksinger Dave Van Ronk wrote, “We were having the time of our lives. We were hanging out with our friends . . . and we were laughing all the time.”[6]

***

In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy forwarded landmark civil rights legislation to Congress. In June 1963, he also gave what the Boston Globe called his most important speech, “A Strategy for Peace” at American University in Washington, DC.

I decided to go to American University.

Hubie and I lived together for two years in the dorm at American University in Washington, DC, before he married his childhood sweetheart in 1969. In our senior year, December 1969, our postgraduate plans were interrupted by the draft lottery. In what could have been our last summer, the summer of 1970, Hubie and I, induced by the draft7 and by the desire to avoid assignment to the infantry, enlisted in the US Army Security Agency Language Program, hoping for a career-advancing and life-prolonging language such as French or Italian or even more Latin (I had studied four years), Instead, I got Vietnamese, Saigon dialect. With similar aspirations, especially as a newlywed, Hubie got Vietnamese, Hanoi/north dialect. We spent the remainder of 1970 together in basic training at Fort Dix and the full calendar year 1971 at the Defense Language Institute, Fort Bliss, Texas. All the while we hoped the war would end soon.

Unsurprisingly, after the completion of the forty-seven-week intensive Vietnamese language course, Hubie and I received orders for Viet Nam. Hubie and his new wife went to Toronto.

I went home to Weymouth for thirty days’ leave before shipping out.

Since 1969, the United States had been giving increased battle responsibility to the Republic of Viet Nam’s Army (ARVN). Officials called this the “Vietnamization of the war.” Critics called it the Vietnamization of the caskets. American troops were being sent home. During the period of February to April 1972, over fifty-eight thousand returned home, the largest troop withdrawal of the war. That left only about sixty-nine thousand American troops in Viet Nam, many of whom made up only two combat brigades and a reduced air force presence. During the period 1966–71, the “net body count” in the war was drastically in the favor of the American and South Vietnamese forces. In mid-1971 that kill ratio swung in the favor of the Viet Cong (VC)/North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and continued until January 1973, when the peace treaty was signed.

Wait, I was about to leave home for a war zone that has just experienced the largest American troop withdrawal of the war, and, at the same time, the enemy—who by all accounts was already winning—began what was described as the fiercest campaign of the war.

The ARVN was losing a regiment a month to AWOLs and desertions. One American wrote home from Viet Nam, “There’s no reason to be here and there is even less reason to see Americans dying here.”[8]

On March 10, 1972, the intrepid 101st Airborne Division drew down from Viet Nam, a poignant signal.

On March 19, 1972, the US bombing of the Ho Chi Min Trail intensified.

On March 23, 1972, the Paris peace talks were suspended.

On March 30, 1972, at about noon, NVA regular units, not surreptitious insurgents, invaded across the demilitarized zone separating North and South Viet Nam, and by April 2, 1972, South Viet Nam hero Colonel Pham Van Dinh surrendered, shocking the rest of the ARVN. By April 23, 1972, the North accomplished incredible victories primarily due to “insufficient and inadequate supply, deficiency in intelligence and tardy deployment of the reserves . . . [the] ARVN leadership was most lacking.”[9] During one battle, an ARVN tank was moved to respond to a nearby NVA roadblock; seeing the tank leave, thinking the worst, panic set in among the ARVN troops who fled.

One of the ten most important battles of the war in Viet Nam, the North’s Easter Offensive, sought to capture Saigon and end the idiotic, multinational, multicentury futility of the American colonial project. The focus of the North Vietnamese strategy was the Saigon–Long Binh–Bien Hoa corridor, a mission similar to the Tet Offensive of 1968. Using the maximum number of NVA military forces, and after considering the Vietnamization of the war in the south and the political climate in the United States, NVA General Vo Nguyen Giap was optimistic that a final march to Saigon would be successful.

Cam Ranh Bay, an R&R resort and site of Bob Hope shows, was known as “about the safest place you could be in April 1972.”[10] On April 9, 1972, the Communists attacked Cam Ranh, killing four Americans and wounding twenty. Three days earlier, the last American combat infantry unit had stood down.

On April 28, 1972, at 0315 hours, while on Mission Number F2A3 on the Flying Tiger Airline and Alaska Airlines, respectively, I checked two baggage pieces totaling sixty-five pounds, and, having been assigned seat number 18, I boarded the flight, destination SGN—Saigon. “On 28 April, the North Vietnamese moved in for their final assault on the now encircled Quang Tri—and panicked civilians began to stream south along Route 1 which was hit indiscriminately, killing thousands of innocent people along the ‘Terror Boulevard.’”[11] In April and May 1972, the NVA pressed a third attack according to the plan to gain Saigon. On April 28, 1972, the day I arrived in Viet Nam, Sergeant Franklin East, First Cavalry, from McComas, West Virginia, died at Bien Hoa airbase, twenty miles north of Saigon. Also on that day, Warrant Officer William Allen Haines Jr. from Warren, Ohio, and Captain Paul Vaughan Martindale from Letohatchee, Alabama, of the Fourth Cav First Aviation Brigade died in a helicopter crash in Quang Tri province and Master Sergeant Roy J. Day of the Vung Tau Army HQ Command from Racine, Missouri, died in Phuoc Tuy province.

I was billeted at Davis Station on Tan Son Nhut Airbase, assigned to the 509th Radio Research Group of the Army Security Agency. One of my former language students, “OJ” Johnson, who had arrived months before me, informed me unofficially that the “VC was kickin’ ass and taking names.” Officially, I learned of the dire battles of An Loc and Quang Tri. I heard the CIA analysis that Saigon survived only because of the intensive air force bombing operations. I learned of some heroic ARVN last stands.

In my first two weeks, there were fifty-nine deaths, thirty-five of which were in nearby Bien Hoa province. In the first month there were eighty total in country.

On June 8, 1972, in Trang Bang, “the girl in the picture” had her clothes melted into her back by napalm dropped by her own country’s air force, another tragic absurdity in the continuing absurd tragedy that was the war. The photo of Kim Phuc has become famous, but to me the just as compelling image is the face of the boy in the left foreground of the photo looking forward in abject terror. Kim’s cousins, an infant and a three-year-old, were also killed. No children should be victims to that inhumanity. No children should witness that. Not by their own people. Not by any people.

On June 9, 1972, the fabled John Paul Vann, military war hero and civilian director of the Agency for International Development, senior advisor for Region II, Pleiku, died in a helicopter crash in Pleiku, enroute to celebrate with troops the victory in holding back NVA at Kontum. Vann, although a civilian, directed artillery and air strikes that saved Kontum. When Vann, the hero of A Bright Shining Lie, died, I realized no one was immune.

On June 17, 1972, a group of burglars ransacked an office in Watergate, answering one of singer Country Joe McDonald’s most important questions, “What are we fightin’ for?” with the obvious answer, “Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn.”

In August 1972, the last ground troops left Viet Nam.

On July 7, 1972, Staff Sergeant Thomas Patrick Keogh, from Philadelphia, 146th Aviation Company, 509th Radio Research Group, my unit, died in Bien Hoa.

The Easter Offensive lasted up to September 15, 1972, when Quang Tri was saved from the NVA attacks but was reduced to dust. Not rubble, dust. It wasn’t until September 30, 1972, that combat operations decreased and another month into October until the area was secured. On November 11, 1972, the United States lowered the American flag at Long Binh and turned the base over to the ARVN. At the time there was a relentless Viet Cong push to influence the Paris peace talks. While living at Davis Station we had two rocket attacks.

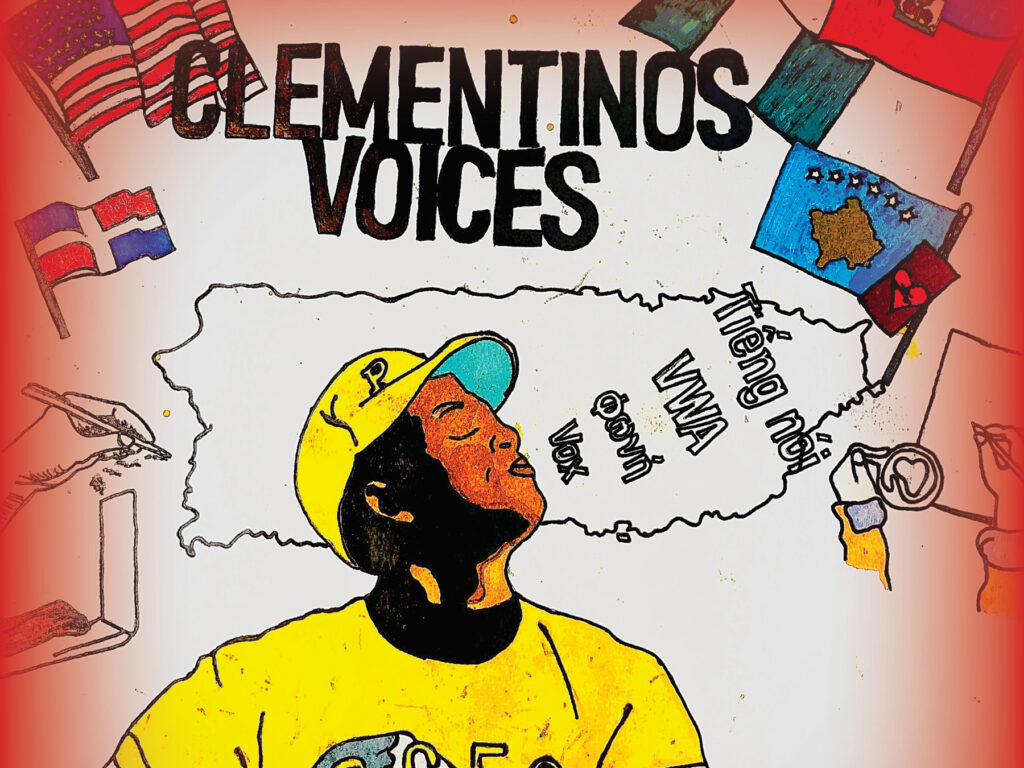

On January 1, 1973, my childhood hero Roberto Clemente died in a plane crash while involved in the airlift of supplies to victims of an earthquake in Nicaragua. It was not lost on me that the upcoming Tet holiday had become a time of VC and NVA military actions.

On January 22, 1973, LBJ died peacefully at his ranch in Texas.

On January 23, 1973, the Paris Peace Accords were signed with the provision that US troops leave Vietnam within sixty days, by the end of March.

I had met the admission requirements of Bill Mauldin’s Benevolent and Protective Brotherhood of Them What Has Been Shot At.12 Fortunately, I didn’t meet the criteria of the Benevolent and Protective Brotherhood of Them What Has Been Shot At. [12] Thank Christ.

On February 23, 1973, Spec Five James Leland Scroggins, 18th Aviation Co, 164th Aviation Group, First Aviation Brigade, from Mulberry Grove, Illinois, became the last army aviation casualty who died, seven days after a helicopter crash on a supply mission for peacekeeping forces in Binh Long province. He also became the last death before all troops left Viet Nam by March 31, 1973.

On February 23, 1973, I left Viet Nam, a few weeks before the official end of American combat operations. There were no American deaths from the day I left through the end of the pullout at the end of March.

At the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, “The Wall,” a flag is flown twenty-four hours a day overlooking the area; at the base are the seals of the five branches of service with the inscription

THIS FLAG REPRESENTS THE SERVICE RENDERED TO OUR COUNTRY BY THE VETERANS OF THE VIETNAM WAR. THE FLAG AFFIRMS THE PRINCIPLES OF FREEDOM FOR WHICH THEY FOUGHT AND THEIR PRIDE IN HAVING SERVED UNDER DIFFICULT CIRCUMSTANCES.

The first casualty of the Viet Nam War was from Weymouth, listed on panel 52E, line 21. The Department of Defense considers the first advisors relative to hostilities in Viet Nam to have begun service on November 1, 1955..One of those advisors was Air Force Technical Sergeant Richard Bernard Fitzgibbon Jr., a World War II Purple Heart recipient and Weymouth resident. On June 8, 1956, Technical Sergeant Richard Bernard Fitzgibbon Jr., 1173rd Foreign MSN Squadron, MAAGV, was handing out candy to kids in Saigon when a deranged fellow American airman shot and killed him, panel 52E, line 21. In my mind, Fitzgibbon the Elder’s legacy is as much based upon how he died—causality officially “homicide”—as opposed to the chronological order of his death, the first, relative to the 58,315 or so others, killed while helping children, an allegory of the idiocy. Sadly, on September 7, 1965, Fitzgibbon’s son, Lance Corporal Richard Bernard Fitzgibbon III, Weymouth High School Class of ’62, Third Marine Division, III MAF, was killed in Quang Tri from an explosive device, two weeks before he was scheduled to come home, panel 2E, line 77. This unfortunate event made them one of three American father-son pairs killed in Viet Nam. Richard B. Fitzgibbon Jr. and his son Richard B. Fitzgibbon III are buried in the Blue Hills Cemetery in Braintree, where both my father and mother are buried in the military veterans section, as are my good friends US Marshal Billy Degan, killed at Ruby Ridge, and Braintree Police Lieutenant Greg Principe, killed on duty.

Specialist Four James Thomas (“Tom”) Davis, radio direction finder operator, Third Radio Research Unit (later the 509th Radio Research Group, my unit), Army Security Group, MAAGV, from Livingston, Tennessee, died as a result of small arms fire on December 22, 1961, in Hau Nghia province, panel 1E, line 4. On January 10, 1962, President Johnson cited Davis as the first battlefield casualty of the Viet Nam War. Davis Station, the Saigon site of at the time approximately ninety troops, became the first military installation in Viet Nam named for a fallen serviceman.

Between my first and last days in Viet Nam, over five hundred American servicemen died. In a way, a young man from Weymouth was in Viet Nam when the first serviceman was killed in the war and when the last was killed in the country before all troops left by March 31, 1973. Dalton Trumbo, in his addendum to the introduction of Johnny Got His Gun,[13] stated, “If the dead mean nothing to us, what of the 300,000 wounded? . . . How many arms, legs, ears, noses, mouths, faces, penises they’ve lost?”

The bullets were as deadly as the rockets’ glare was red.

“Servicemen from Dorchester were four times more likely to die in Vietnam than those raised in fancy suburbs.”[14]

“The latter stages of American involvement in Vietnam largely have been ignored. . . . There were only 759 American deaths in 1972.”[15] Only.

As Liam Clancy sang about the horrors of the 1915 Battle of Gallipoli in “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda,” “the living just tried to survive.”[16]

Daniel Ellsberg said we weren’t on the wrong side; we were the wrong side.

In his 1996 song, “When a Soldier Makes It Home” (from the album Mystic Journey), Arlo Guthrie sang:

Halfway around the world tonight

In a strange and foreign land

A soldier unpacks memories

That he saved from Vietnam

The night is coming quickly

And the stars are on their way

As I stare into the evening

Looking for the words to say

That I saw the lonely soldier

Just a boy that’s far from home.[17]

***

Doing what I was supposed to do—appreciating the great opportunity to live and work and study in Washington, DC, to develop plans for the next stages of my life—I had seven years taken from me by my government without just cause. I did not give up. I did not try to kill it to save it. I joined the very government—not a deep state, but a flawed government—to which I devoted thirty-four years. I turned two and a half years of servitude—servitude enforced and supported by lies of the government—into decades of service to my country, saving countless lives and helping fellow Americans flourish according to promises made centuries ago by their government.

Since 1973, the year I left Viet Nam, the panels on a wall at the entrance to JFK’s Presidential Library have exhibited a number of his most inspiring quotations. The first words displayed are from his American University speech—ahead of the most memorable seventeen-word exhortation (“Ask not what your country can do for you . . .”) from his Inaugural Address: “Every person sent out from a university should be of his or her nation as well as of his or her time, and I am confident that the men and women who carry the honor of graduating from this institution will continue to give from their lives, from their talents, a high measure of public service and public support.”

More than three decades later, I had tickets for an American Airlines flight from Logan Airport, Boston, Massachusetts, to George Bush International in Houston, Texas.

Usually the room in Plymouth, Massachusetts, was set up as a small family restaurant run by the two brothers Donovan and Patrick, who alternated cooking and waiting on tables. Tonight, though, the boys had fashioned an aisle of two rows of chairs and the Fisher-Price toy kitchen as a jet cockpit ready for takeoff instead of the usual food preparation. Donovan was pilot and Patrick copilot for this flight, each outfitted with one of Daddy’s official-looking scally caps. Their toy washing machine became the airliner’s control panel. There was only one window seat. After dutifully storing their luggage (actual Spiderman rolling suitcases used during their last trip to Texas) and checking my ticket (a receipt from the Massachusetts Lottery Megabucks), they took off. Well, barely took off, until Patrick added two AAA batteries to the long line of batteries Donovan had unsuccessfully added to the engine compartment to increase power.

When Donovan told me we were going from Boston to California to Texas, I questioned why I had booked this flight. He motioned to the nearby GPS (a globe from his desk) and said we were not going there, pointing to China. There was mention of Mars and asteroids.

We had a pretty safe flight until copilot Patrick got up to pee and, shortly thereafter, his pilot Donovan also got up to follow. As a nervous flier, I yelled, “Hey, hey, where are you going!” I figured it would be a teaching moment, so while they were standing in the aisle, far away from the controls, I asked them sternly, “Do you know why both the pilot and copilot can’t get up at the same time?” Without hesitation, Donovan replied, “Yes, because there’s only one toilet.”

After a very safe landing, we three went up to the bedroom where Bindi was organizing her animal specimens and Bruce was positioning Star Wars guys while Laila and Madison and Amelia were jumping on Nana’s bed in violation of the rule: no more monkeys jumping on the bed. Donovan and Patrick separated, one joining Bruce and Bindi and the other joining the girls’ group jump. Julia, Leo, Charlotte, and Beckett had not arrived yet.

I stayed for a moment taking in the scene and spontaneously blurted, “I love you kids.”

A child’s voice found its way out from the laughter, “We love you, too, Grandfather.”

On April 23, 2015, Luke Franey, with whom I attended the Federal Law Enforcement Academy, by now the Special Agent in Charge of the United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, Denver Field Division, reflected twenty years after the murder of children and other civilians at the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. He told USA Today, “Be a better person. Be a better agent. Be a better husband. Be a better dad. Be a better law enforcement officer, try to prevent these events from happening.”[18]

____

[6] Dave Van Ronk, The Mayor of MacDougal Street (Cambridge, MA: DaCapo Press, 2005), 213.

[7] A term developed by Christian Appy, Patriots (New York: Viking, 2003).

[8] Bernard Edelman, ed., Dear America: Letters Home from Vietnam. Vietnam Veterans Commission (New York: W.W. Norton, 1985) Letter dated July 2, 1970, 227–28.

[9] Albert Grandolini, The Easter Offensive Vietnam 1972, vol. 1 (West Midlands, England: Helion, 2015), 33.

[10] Jim Smith, Heroes to the End: An Army Correspondents Last Days in Vietnam (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, 2015), 239.

[11] Grandolini, The Easter Offensive, 34.

[12] Bill Mauldin, Up Front (New York: Henry Holt, 1945), 100.

[13] Dalton Trumbo, Johnny Got His Gun (New York: Bantam Books, 1970).

[14] Lois P. Rudnick, ed. American Identities: An Introductory Textbook (New York: Wiley, 2005), 139, quoting Christian G. Appy, Working Class War.

[15] Smith, Heroes to the End, vii.

[16] Liam Clancy, music and lyrics by Eric Bogle, “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda” (Larrikin Music Ply Limited, Sydney, Australia, 2000).

[17] Arlo Guthrie, “When a Soldier Makes It Home” (BMG Rights Management, 1999). USA Today, “Man in Iconic OKC Bombing Photo Breaks Silence,” April 23, 2015.

[18] USA Today, “Man in Iconic OKC Bombing Photo Breaks Silence,” April 23, 2015.