Historians, artists, engineers, and more are expanding the stories of the commonwealth in innovative ways Catalyzing civic engagement – Framingham History Center In 2024, the

“Voices and Votes: Democracy in America” is on tour in Massachusetts from April 2025 through January 2026. It is a collaboration between the Smithsonian, Mass Humanities, and six host sites across the commonwealth. As part of the Smithsonian’s Museum on Main Street program, Mass Humanities partnered with host sites in Ashby, Douglas, East Sandwich, Holbrook, Lee, and Shelburne Falls to bring a world-class exhibition to rural communities.

Individuals throughout Massachusetts’ history have raised their voices, marched in protest, signed petitions and written powerful pieces to work for change in their communities. This digital exhibit highlights nine individuals who had a powerful effect on democratic rights in the commonwealth. Scroll through our timeline to learn more about these fascinating leaders!

We’d love to hear stories of people in your community who have raised their voices for change! Share on social media and tag us with #VoicesandVotesMA!

William Apess was a Pequot and Mashpee Wampanoag Methodist minister. In 1833-34, he led the Mashpee Wampanoag community in a successful effort to regain their tribal sovereignty. This event is sometimes called “the Mashpee Revolt.”

In the 18th century, the state government appointed white "overseers" to govern the Indigenous community in Mashpee. The overseers failed repeatedly to protect Indigenous land. White settlers trespassed on the land and stole resources, including firewood and shellfish.

Apess arrived in Mashpee in 1833. He helped the Mashpee organize a 12-person council and draft a formal protest against the overseers. White farmers confronted the Mashpee to test the community’s resolve. The confrontation was not violent. However, Apess and several other Native men were arrested. Apess served 30 days in jail.

In 1834, Apess, the Mashpee, and their allies convinced the state to restore the Mashpee Wampanoag’s right to self-government.

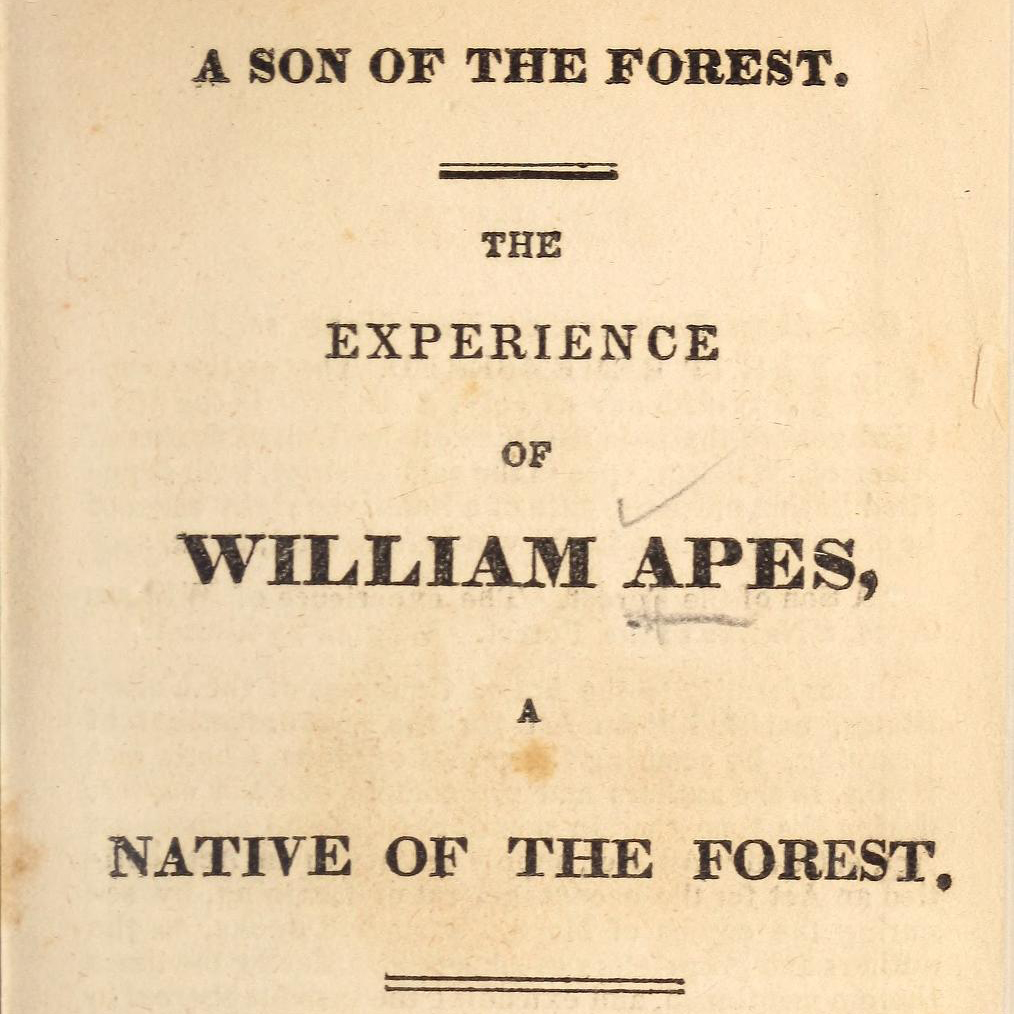

Apess also authored the first autobiography written by a Native American, A Son of the Forest (1829). He died in 1839.

Today, the Mashpee have the largest Native population in Massachusetts.

Image credit: Title page of "A Son of the Forest" (1829).

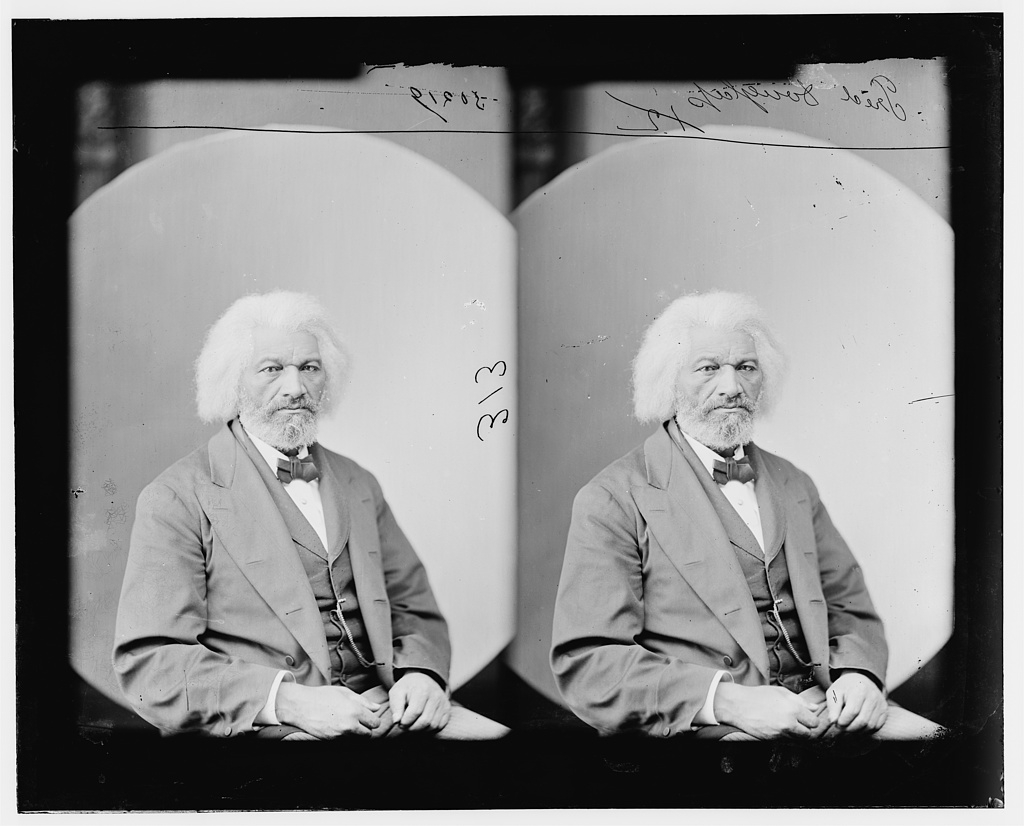

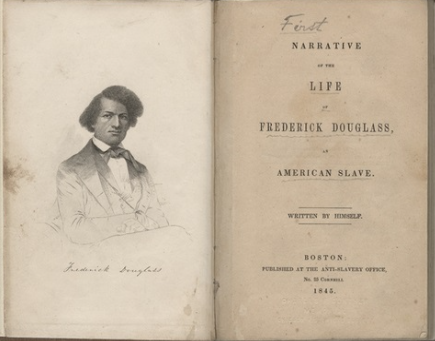

Frederick Douglass was an advocate against slavery and for racial justice. Millions of people around the world heard or read his powerful speeches and writings.

Douglass taught himself to read and write as a child. On September 3, 1838, when he was 20 years old, Douglass freed himself from slavery in Maryland. He found his first paying work in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

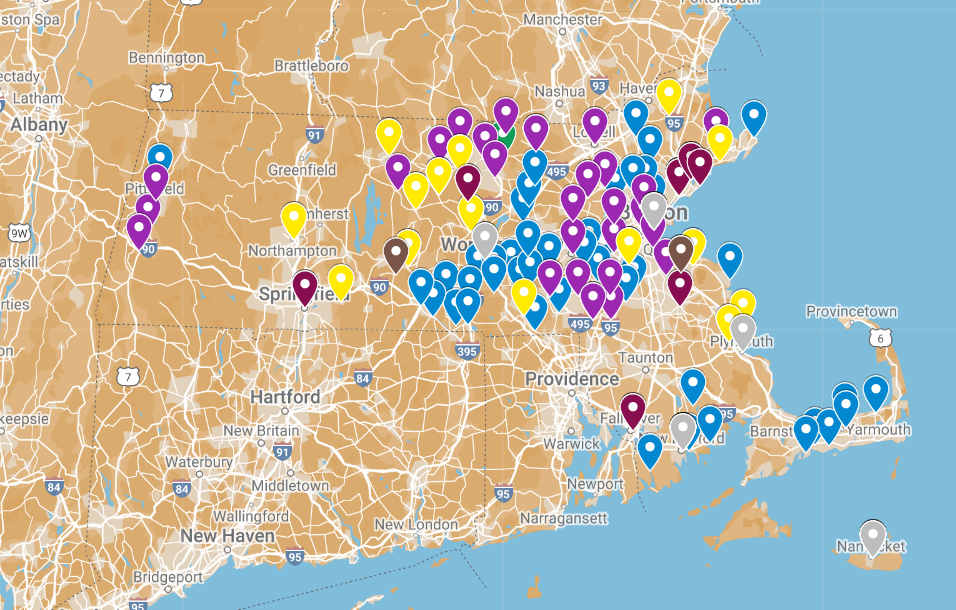

In the 1840s, Douglass became involved in the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts. He traveled across the state and country and gave hundreds of anti-slavery speeches. He also advocated for women’s right to vote. (View our interactive map to see if Douglass spoke in your hometown).

Douglass published his autobiography, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, in 1845. He traveled to Ireland for two years to avoid being captured and sent back to slavery. Fellow abolitionists purchased his freedom, and he returned to the US. In 1855, he began publishing an anti-slavery newspaper called The North Star.

The Civil War ended in 1865, and the 13th Amendment abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime. Frederick Douglass continued to advocate for equality for African Americans and emphasized the importance of exercising the right to vote in his speeches.

Frederick Douglass died in 1895.

Watch our short documentary film about the history of public readings of Douglass' famous speech, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"

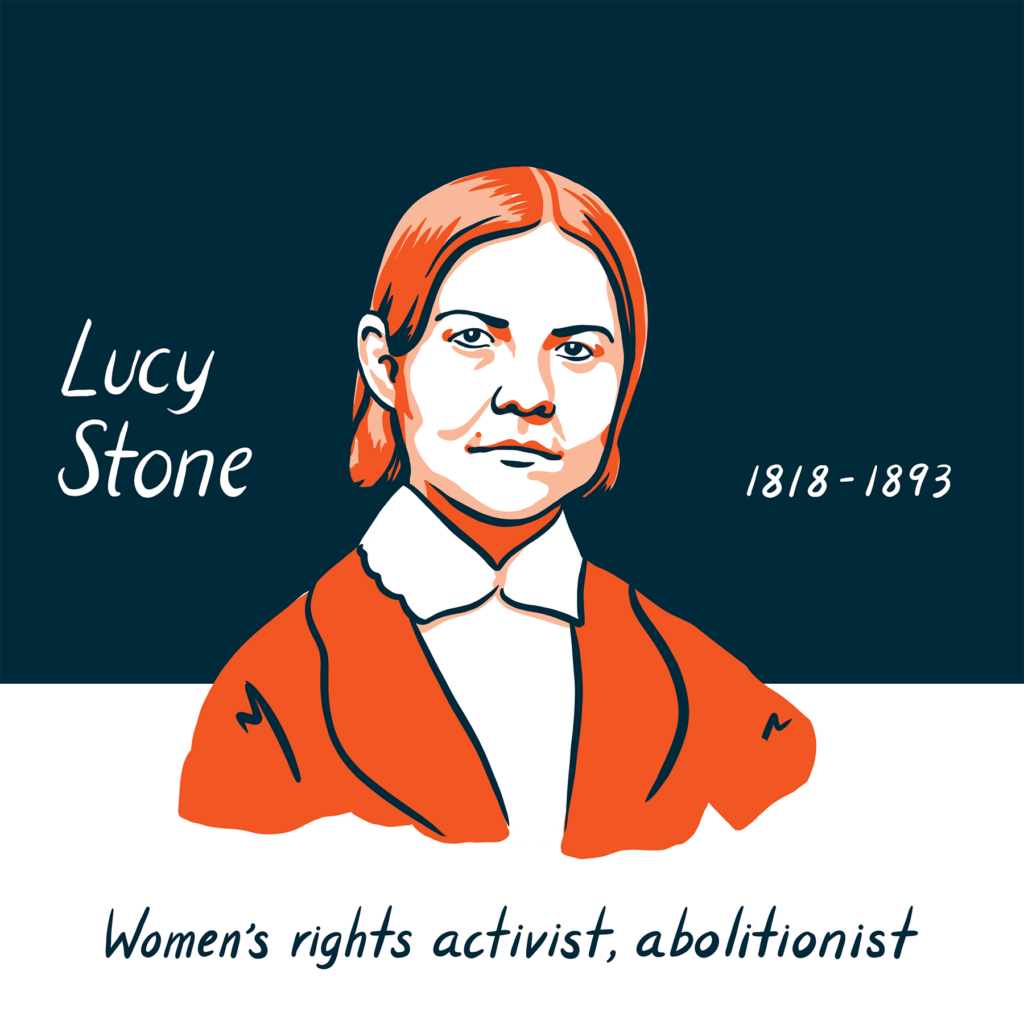

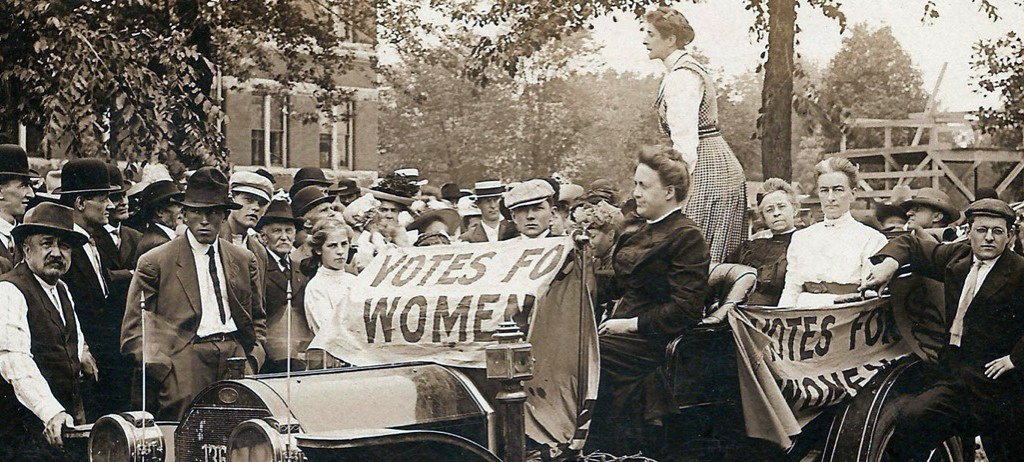

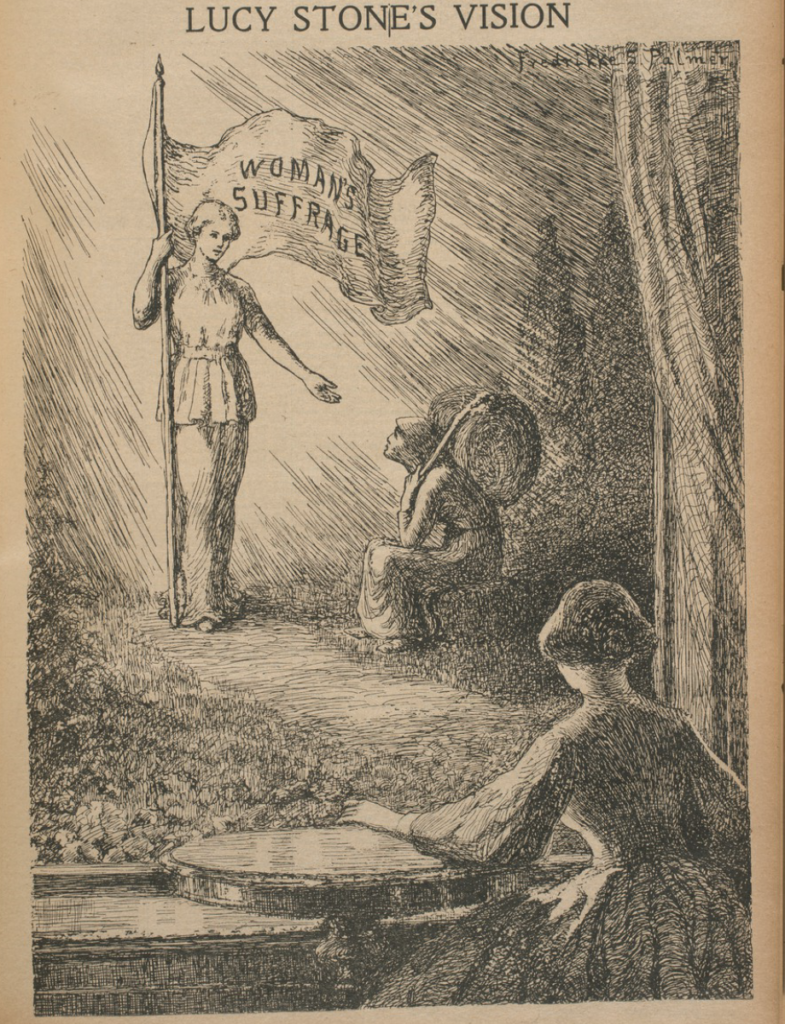

Lucy Stone was an abolitionist and a suffragist. She was also the first Massachusetts woman to earn a college degree. She was one of nine children. Her father encouraged her brothers to go to college, but not Lucy. When she was sixteen, she began working as a teacher to earn money to go to college. In 1843, at the age of twenty-five, she began her education at Oberlin College in Ohio. When she graduated in 1847, Oberlin asked her to write a commencement speech that a man would read in her place. Stone refused.

After she graduated from Oberlin, Lucy Stone began working for William Lloyd Garrison, an abolitionist organizer and publisher. She traveled the country giving speeches against slavery and for women’s rights. In 1850, she organized the first national Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. Over 1,000 women from eleven states attended the convention, making it much larger than the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

Throughout her lifetime, Lucy Stone advocated for everyone to have equal access to voting rights regardless of race or gender. Her approach was different from her fellow suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who believed that white women should get the vote before African Americans. As the head of the American Women’s Suffrage Association, Lucy Stone authored articles, gave speeches, and edited the AWSA magazine, the Woman’s Journal. She died at age 75 in 1893.

Image credits: Illustration from the Women's Journal, 1915, courtesy of the National Park Service.

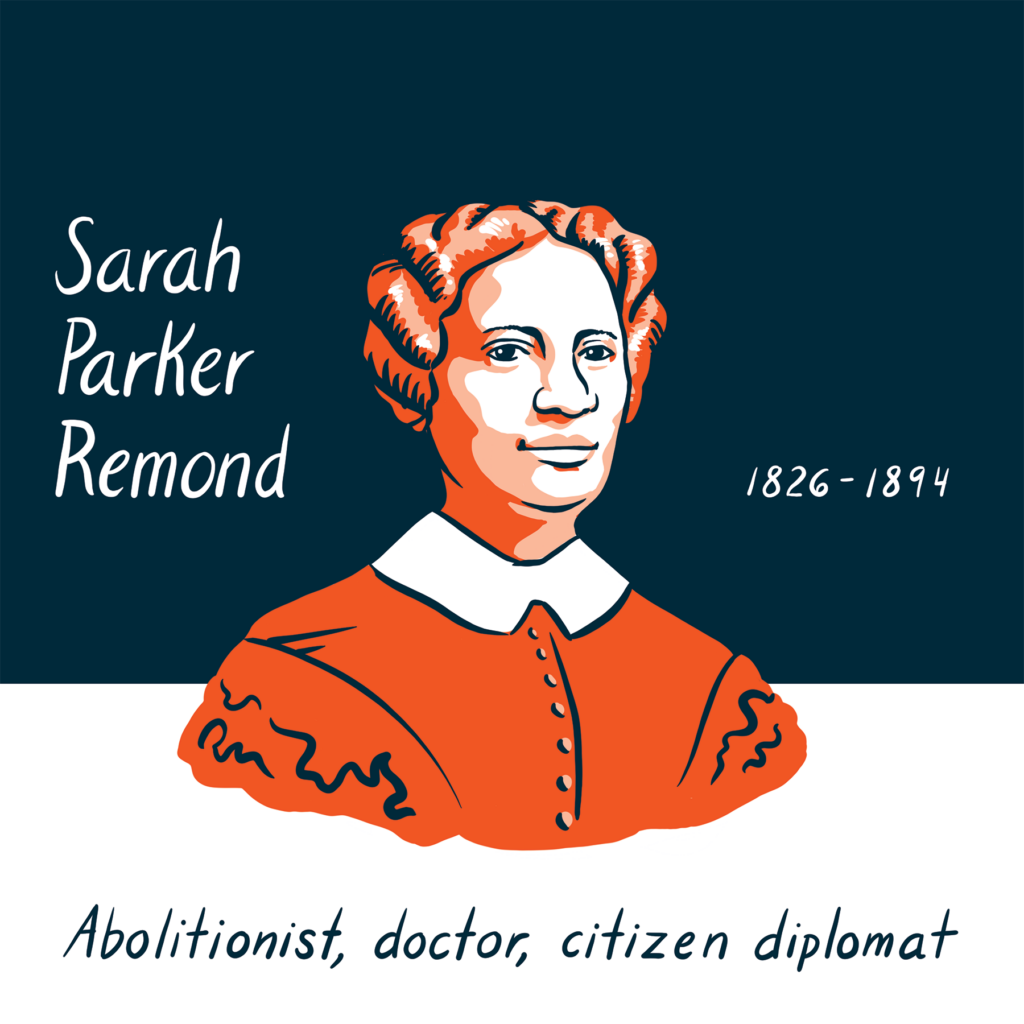

Sarah Parker Remond was an African American activist. She was born in Salem, Massachusetts, in 1826. Her parents were both free African American activists. Remond was an outspoken advocate against slavery and racism. As a child, she was expelled from a school because of her race and forced to attend a segregated school. Remond gave her first public lecture against slavery in 1842, at the age of sixteen.

In 1853, Sarah Parker Remond was at the theater in Boston with her sister when a theater worker demanded that they sit in the segregated section. Remond refused, and told the worker they would sit in the seats they paid for. The worker called for a police officer, who forced her to leave the theater and pushed her down a flight of stairs. Remond charged the theater worker and the police officer with assault, and the officer and the theater worker were both found guilty. However, they only had to pay a fine of $1.

In 1859, Sarah Parker Remond traveled to England to give abolitionist speeches. As a “citizen diplomat,” she helped convince workers in the English cotton mills to support the Union instead of the Confederacy in the Civil War. She also attended college while she was in London. In 1867, she moved to Florence, Italy, where she could continue her education without the restrictions of systemic racism. She completed her medical degree at the Santa Maria Nuova Hospital school. For the next twenty years, she practiced medicine as an obstetrician. After a long life as an international activist and doctor, Remond died in Rome in 1894.

Image credit: Portrait of Sarah Parker Remond courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was born in Boston, in the free African American community on Beacon Hill, in 1842. Ruffin began her career in activism by recruiting African American men for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments while she was in her late teens and early twenties.

After the Civil War, Ruffin joined the Massachusetts Suffrage Association in 1870. She worked tirelessly to organize African American women. She founded some of the nation’s first organizations where Black women could come together and work towards common goals.

In 1890, she launched the Woman’s Era. This newspaper published stories on women’s rights, racial inequality, and women’s suffrage. Ruffin wrote articles for the paper and was its publisher. Unfortunately, the paper closed in 1897. In 1895, she founded the National Federation of Afro-American Women, which merged with another organization in 1896 to form the National Association of Colored Women. The NACW campaigned for women’s rights, including the right to vote, and advocated for racial equality and justice. Ruffin also helped establish the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1912.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin never stopped speaking and writing about the intersection between women’s suffrage and racial inequality. She lived to see the passage of the 19th Amendment, granting women the right to vote, and died in 1924.

Image credits: Portraits of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, courtesy of the New York Public Library. Front page of "The Woman's Era," September 1894, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Let us know about your experience at “Voices and Votes” by taking our visitor survey.

Jennie Loitman Barron was born in Boston in 1891. Her parents were Russian Jewish immigrants, and she began working at the age of twelve. At age fifteen, in 1906, she enrolled at Boston University. She was an excellent student, and taught classes for immigrants at night to pay her way through school. While she was a freshman at BU, she organized the BU Women’s Suffrage Association. She also spoke out for suffrage on street corners, talking to anyone who would listen.

After she graduated from college, Barron attended BU Law School and graduated in 1914. She opened her own law practice in Boston and continued to advocate for women’s suffrage. After the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, she worked with the League of Women Voters to fight for women’s political rights. As a lawyer, she advocated for women’s rights in the workplace, equal pay, and women’s right to sit on juries. She argued that it was unfair that a woman could have the right to vote and hold office but not the right to participate in the justice system as jurors. In 1950, women were allowed to join juries in Massachusetts, thirty years after they gained the right to vote.

Jennie Loitman Barron was a trailblazer for women lawyers in Massachusetts. In 1924, she was the first woman appointed assistant attorney general. In this position, she was the first woman to prosecute major criminal cases in Massachusetts. In 1959, she became the first female judge on the Massachusetts Superior Court. She served there until she died in 1969.

Image credits: Judge Jennie Loitman Barron shaking hands with Massachusetts Governor Charles Hurley during her swearing-in ceremony for the Boston Municipal Court, December 1937, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Jennie Loitman Barron is sworn in as a judge, December 1937, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

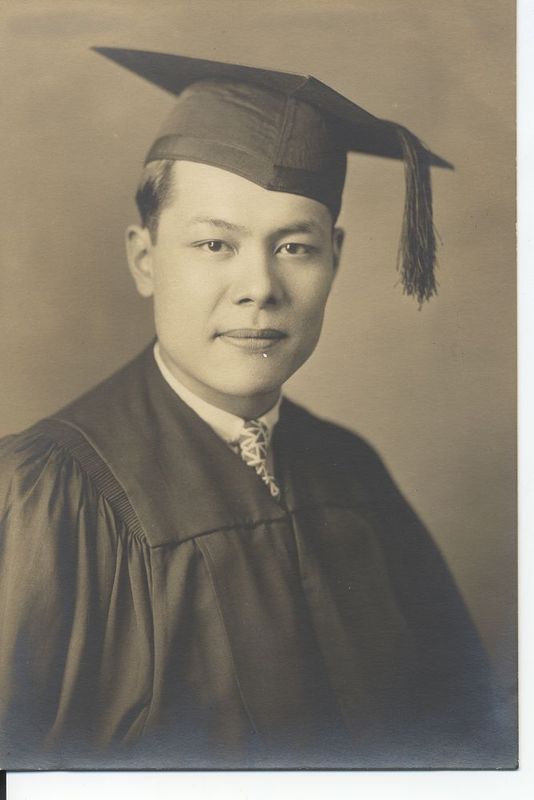

Harry Hom Dow was born in Boston in 1905. His parents were immigrants from the Taishan district of China. Harry Hom Dow worked his way through school, helping keep the family laundry business going. He attended Suffolk University Law School and graduated in 1929. He was the first Chinese American to be admitted to the Massachusetts Bar and practice as a lawyer in the state.

Dow focused on immigration issues and worked for the federal government in New York City for the first part of his career. He volunteered for military service during World War II. After the war, Dow opened his own immigration law practice. He was caught up in the Red Scare of the early 1950s. Because China was a Communist nation, Chinese Americans came under intense and unfair scrutiny. Dow’s professional reputation was damaged, and he had to close his New York law practice in 1960.

He returned to Boston. For twenty years, he volunteered to provide legal aid to the Chinese American community in Boston. He was especially involved in the fight to protect the South End neighborhood from Boston’s urban renewal projects. The city wanted to tear down large parts of the neighborhood and build housing for wealthy people. Dow and his fellow activists successfully stopped these efforts. Dow also inspired other members of the Chinese American community to get involved in local politics. He advocated for his neighborhood until the end of his life. Harry Hom Dow died in 1985, at the age of eighty.

Image credit: “Harry Hom Dow's graduation portrait, 1929,” Harry Hom Dow Papers, 1911-1985 (MS 111), Moakley Archive & Institute, Suffolk University, Boston.

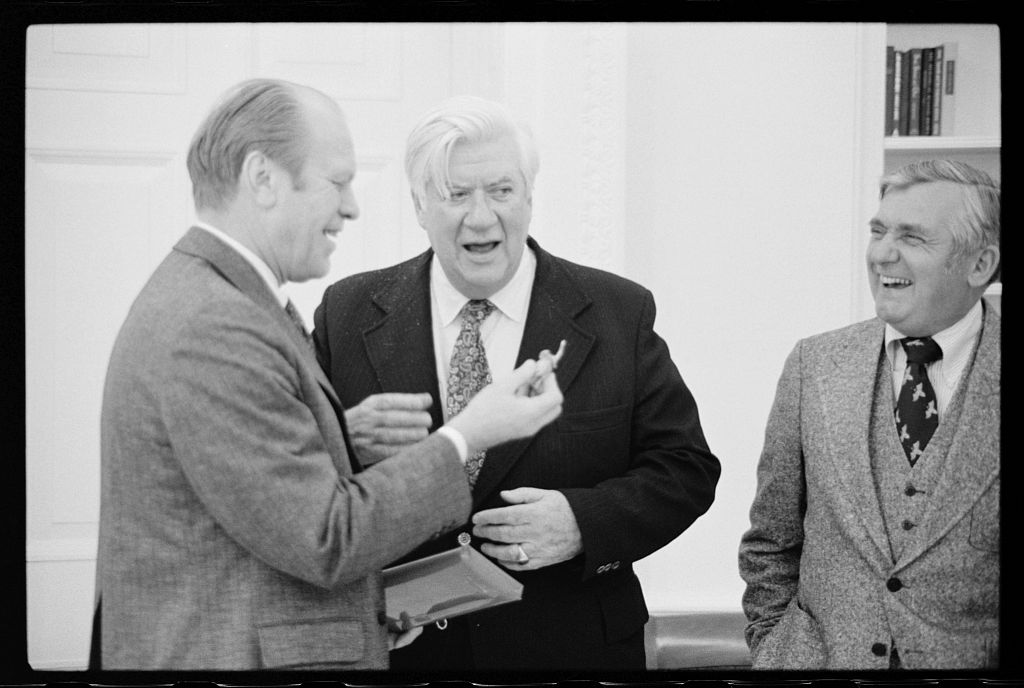

Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1912. He grew up in a working-class household. He got involved in politics at the age of fifteen, when he volunteered for Al Smith’s 1928 presidential campaign. He graduated from Boston College in 1936 and won his first election to the Massachusetts state legislature in 1937. He stayed in the state legislature until 1952, when he was elected to the House of Representatives.

O’Neill’s experiences growing up during the Great Depression and his interpretation of his Catholic faith led him to believe that it was the government’s job to protect and support the American people. He supported universal healthcare and jobs programs and opposed the Vietnam War. He climbed through the ranks and became Speaker of the House in 1977.

O’Neill worked in Congress to expand social support services. He also helped negotiate peace in Northern Ireland. He retired from the House of Representatives in 1987. President George H.W. Bush awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1991. He died in 1994.

Image credit: President Gerald Ford meeting with Tip O'Neill and friend at the White House, Washington, D.C., February 6, 1975, image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Joe Labriola was born in New Jersey in 1945. He joined the US Marines in 1965. Labriola was awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star after being severely wounded in combat in Vietnam. He was also exposed to Agent Orange, an extremely toxic chemical used to kill plants and leaves in the jungle, during the war.

After he finished his tour of duty, he served as a Marine recruiter in Brockton, Massachusetts. He left the Marine Corps in the early 1970s. He was accused and convicted of murder in 1973 and sentenced to serve life without parole. He maintained his innocence his entire life.

In 1997, Joe Labriola and another inmate, Michael Shea, formed the first political action committee (PAC) for prisoners. Labriola believed that using the power of the ballot would give prisoners the opportunity to advocate for change in prisons without using violence. Paul Cellucci, Governor of Massachusetts, banned the PAC. Prison officials searched Labriola’s cell, and he was put in solitary confinement for being one of the leaders of the PAC. Later that year, Governor Cellucci proposed a constitutional amendment that stripped incarcerated people of their right to vote. The amendment passed in 2000.

Joe Labriola remained in prison until 2019. He suffered from lung disease caused by Agent Orange. He continued to advocate for the rights of incarcerated people. He campaigned for better living conditions and for the rights of incarcerated veterans. He also volunteered with Toys for Tots and other charity organizations from within the prison, and published a book of poetry about his time in Vietnam. He was released because of his illness in 2019 and passed away in 2020.

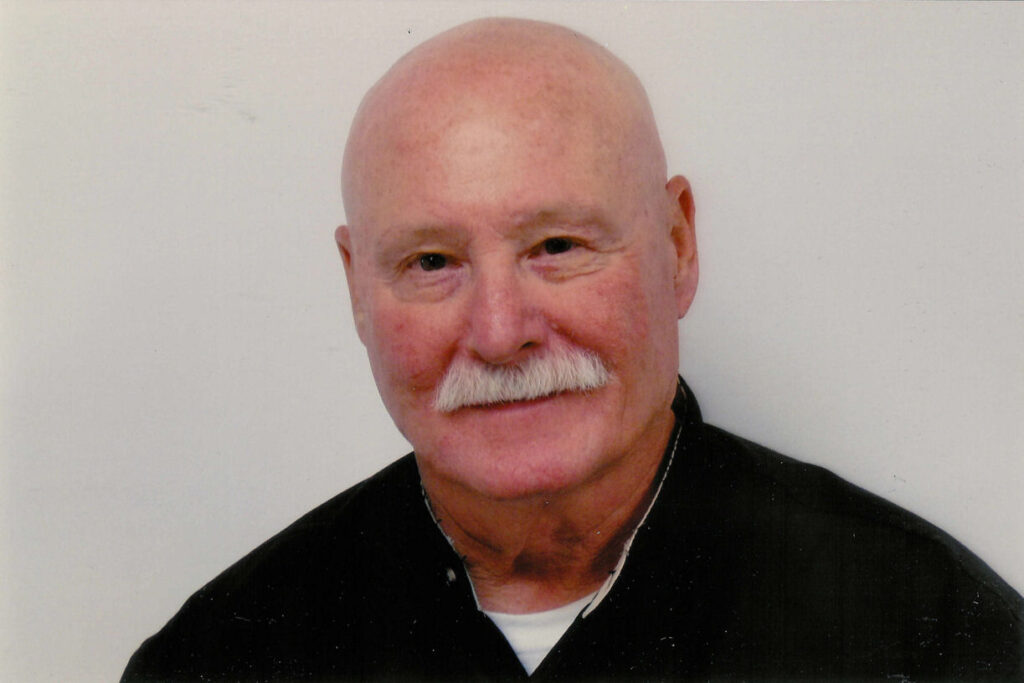

Image credits: Joe Labriola receives the Bronze Star award for heroic service, 1966.

Joe Labriola, 2010.

Joe Labriola at Deer Island after his release, 2019.

All images courtesy of Jim LaPierre and FreeJoeLab.

Historians, artists, engineers, and more are expanding the stories of the commonwealth in innovative ways Catalyzing civic engagement – Framingham History Center In 2024, the

Creative Sector Day 2025 took place at the Massachusetts State House on April 30. Aerialists, musicians, artists, policymakers, youth performers, photographers, dancers, and more gathered

The “Lowell Latinx Archive” is an oral history and photography project created by the Latinx Community Center for Empowerment (LCCE) in Lowell. We recently sat

Mass Humanities

66 Bridge Street,

Northampton, MA 01060