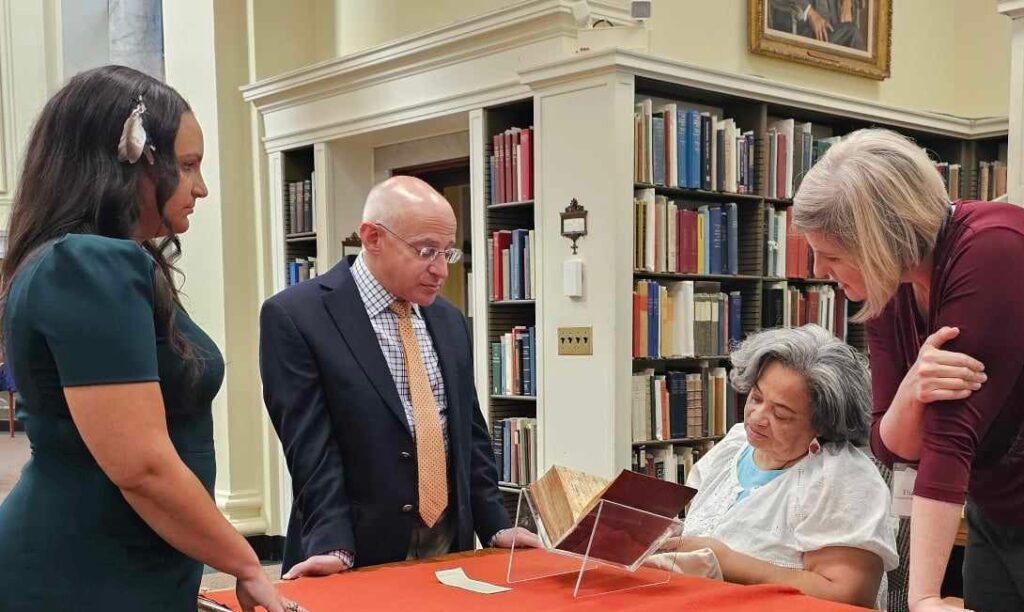

Brittney Walley currently serves on the board of directors for Mass Humanities.

On the seventeenth of September I took an oath to join the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities’ board of directors as a governor’s appointee. To complete this process, I swore in with a 1663 copy of the Algonquian Bible. This bible is a layered piece of cultural material. In the seventeenth century, it was a tool of colonization, but I believe it has been transformed by the very people(s) it once aimed to convert.

While some know this version of the bible as “The Eliot Bible” and credit it fully to missionary Reverend John Eliot, the translation of the Algonquian Bible was made possible through Indigenous people such as Cockenoe, Hiacoomes, Job Nesuton, John Sassamon, Wowaus (also known as James Printer), and potentially others whose names and influences were once known. The Indigenous people involved in the translation and printing of this bible may not have always had the ability to choose their own directions, but today we do. Every day I see my tribe and sister tribes not only maintain cultural continuity but also extend awareness and education about it, about us. I am honored to share this life and Earth with so many robust storytellers. Our stories matter — they always have, and they always will.

Countless people have taken oaths on books of faith throughout history to acknowledge their new responsibilities through their religious beliefs. More recently, oath takers have used a wide range of contemporary texts to acknowledge their accountability through what matters most to them. Because this particular bible contains our language, was typeset by Wowaus, a Nipmuc ancestor, bore witness to many other ancestors, and is now a tool of language revitalization, it made sense to engage with it in this way. I hope to bring a Nipmuc perspective to Mass Humanities, but without the community of the past and present generations I would not be able to bring a Nipmuc perspective anywhere!

While people in the seventeenth century likely did not foresee a bible being used to revitalize Indigenous cultures, it is intrinsically a word bank or dictionary. Finding utility of things originating outside of one’s culture is a traditional local practice. With this in mind, it’s understandable that the Algonquian Bible became a tool of language revitalization. Language is often a precious element of culture and, thus, identity. When we, as first contact nations, engage with and speak in our languages, we keep our cultures alive despite over four hundred years of oppression. When we practice our traditions, we become living proof that our people and our cultures are still here, centuries after colonization and genocide began. When our cultures are a part of our identities, we honor those who died for us while defending our homelands and lifeways, and we honor the future generations yet to come.

I hope my perspective as a Nipmuc will help Mass Humanities to support Indigenous Peoples in Massachusetts and that my experiences allow me to become a sincere ally to others whose stories I may not yet know.

Finally, I hope to share my excitement in joining the board of the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities as its first Indigenous member. I am excited for what’s ahead!

Kuttabotamish newutche, Sonksq Cheryll Toney Holley, for meeting me in this moment and supporting me in this new responsibility.

Many thanks to Scott Casper, Elizabeth Pope, and those at the American Antiquarian Society who helped bring this moment to fruition.

My gratitude extends to Brian Boyles and Governor Maura Healey for this appointment.