With so much media that demands to be consumed right now—newspapers and magazines, books and blogs, the infinite scroll of social media, documentaries, YouTube, podcasts, NetFlix, breaking news, and more, more, more—why spend your precious time reading obscure middlebrow literature published in the first half of the twentieth century?

For one thing, a lot of it is very well written. And it may just let you rest for a moment and make some sense of the world. As the literary scholar Gordon Hutner writes in What America Read: Taste, Class, and the Novel 1920-1960, this “middle-class realistic” fiction called middlebrow provides “a rudimentary vision of some relative cohesiveness of American life, a shareable set of values and questions about the world in which middle-class Americans live.”

In previous posts (“Rediscovering Middlebrow,” November 21, 2018) and “Edna Ferber’s Cimarron, December 20, 2018), I discussed how the work of 20th century middlebrow writers is in danger of being forgotten, but shouldn’t be: they still have much to say to present-day readers. Another middlebrow writer waiting to be rediscovered is Stephen Vincent Benét (1898-1943), whose body of work includes the book-length narrative poem of the Civil War John Brown’s Body (1928) and the classic short stories “The Devil and Daniel Webster” (1936) and “By the Waters of Babylon” (1937).

—

The north and the west and the south are good hunting grounds, but it is forbidden to go east. It is forbidden to enter the Dead Places. But I am a priest and the son of a priest and we can venture there alone. (“By the Waters of Babylon,” 1937)

They came up over the pass one day in one big wagon—all ten of them—man and woman and hired girl and seven big boy children, from the nine-year-old who walked by the team to the baby in arms. Or so the story runs—it was in the early days of settlement and the town had never heard of the Sobbin’ Women then. But it opened its eyes one day, and there were the Pontipees. (“The Sobbin’ Women,” 1937)

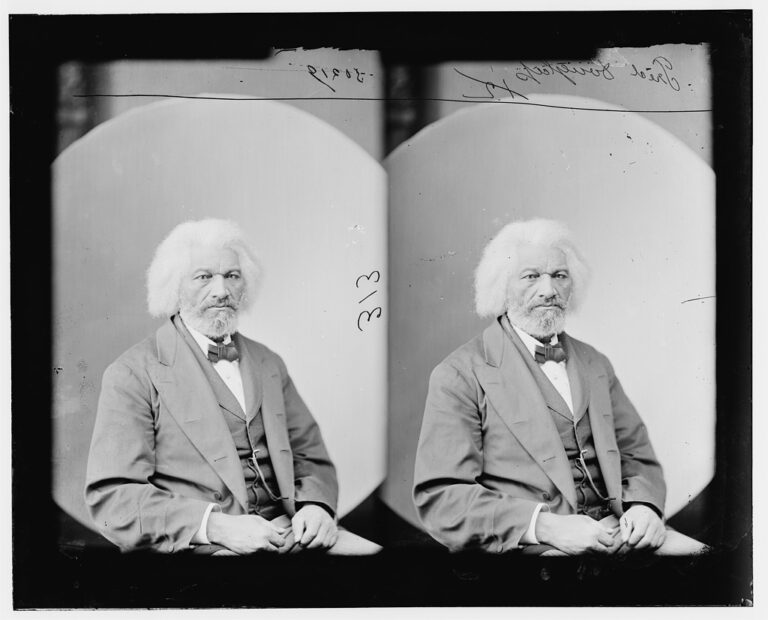

It’s a story they tell in the border country, where Massachusetts joins Vermont and New Hampshire. Yes, Dan’l Webster’s dead—or at least they buried him. But every time there’s a thunderstorm around Marshfield, they say you can hear his rolling voice in the hollows of the sky.” (“The Devil and Daniel Webster,” 1936)

While you’re wondering who these people are and what’s going to happen to them, the one sure thing is that they are Americans. You can’t read Benét without recognizing his faith in the promise of the United States. Born in 1898 into a military family in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, he published his first book of poetry at 17, and continued publishing fiction and poetry prolifically until he died of a heart attack at age 43. His era was the 1920s and 1930s. In spite of the First World War and the Great Depression, those years in many ways marked the end of America’s national innocence. His characters included WASPs, Jews, Irishmen, Yankees, and African Americans. Each of them was unique, and most were fundamentally decent people who believed they would succeed through hard work and pluck.

And succeed they did. Even Jabez Stone, who sells his soul to the devil in “The Devil and Daniel Webster,” is not so much “a bad man as an unlucky one.” There was room for him, too, in Benét’s America.

That doesn’t mean Benét was naive. The characters in “Everybody Was Very Nice,” the story of a disintegrating marriage, prefigure the empty suburbanites of John Cheever’s mid-century fiction. “The Devil and Daniel Webster” deals with the struggles a great man faces when he is tempted to replace duty with personal ambition. “William Reilly and the Fates” is the story of a young midwestern journalist whose bedrock faith in Mom, Apple Pie, and the American Way is challenged when he gains insight into the interconnectedness of humanity during an afternoon at a very curious carnival.

And Benét’s masterpiece, “By the Waters of Babylon,” perfectly prefigures the horror of nuclear warfare decades before the atomic bomb was developed. I reread that story a few months ago, more than eighty years after it was written. Every word still rings true. The language is contemporary. You could still almost use it as a street map to find your way around lower Manhattan. Benét didn’t fool himself about the dreadful possibilities inherent in humankind’s self-destructiveness, but his eternal optimism breaks through in the last lines, when the narrator realizes that the Place of the Gods destroyed in the Great Burning was really a city of men:

And when I am chief priest…we shall go to the Place of the Gods—the place newyork…We shall look for the images of the gods and find the god ASHING and the others—the gods Lincoln and Biltmore and Moses. But they were men who built the city, not gods or demons…They were men who were here before us. We must build again.

Behind the elegant simplicity of Benét’s language is a sophisticated mind and an original point of view. If I could bring only one book to that proverbial desert island, I’d chose his collection of short stories Thirteen O’Clock: Stories of Several Worlds. Some of them—unfortunately, not all—are available on the internet. I recommend finding them.

More than 75 years after his death, we may have lost Benét’s innocent confidence in America. We shouldn’t lose him as well. Do not forget this writer.